The Reservoir Fence & The History Of Silver Lake Reservoir Access And Advocacy

- Eric Brightwell

- Oct 23

- 14 min read

Updated: Dec 3

Summer is here. As we now embrace (or brace ourselves for — depending on your orientation) months of unrelenting sunshine and heat, many of us will, no doubt, dream of cooling off in a pool or at the beach. Of course, Silver Lake has neither public pools nor beaches… but it does, rather famously, have a certain reservoir for which it’s both well-known and named.

Everyone who visits the Silver Lake Reservoir knows that there is no access to the water today. If they somehow don’t, the tall fence should make it abundantly clear. It may surprise many readers to learn, then, that in its early years, swimming and fishing were not just allowed, they (especially the latter) were actively promoted.

Since the decommissioning of the reservoir, there has been a spirited debate about the complex’s future. Most of the disagreement centers around questions of access. Will there be boats? Where will motorists store their cars? Will the fence come down?

There have been numerous reader requests asking me to tackle the thorny topic for quite some time. I have, thus far, avoided answering them – not because they are not valid — but because I don’t particularly wish to end my days strolling through this metaphorical minefield.

On the other hand, though, having opinions about what role the reservoir should serve in our community have been at the center of debates for as long as the reservoir has existed. Arguing about the reservoir, one might say, defines us as Silver Lakers.

So here I foolishly rush, where angels fear to tread.

PREHISTORY

Historically, the site of the reservoir and Silver Lake, supported seasonal wetlands that would’ve teemed with a variety of native flora, fauna, and fungi. For the Tongva, who some 3,500 years ago migrated here from the Sonoran Desert, this generally semi-arid, this comparatively lush landscape would’ve certainly proven an excellent place to forage and hunt for food. The area that’s now Silver Lake, in particular, no doubt teemed with life, sitting atop the watersheds of both Ballona Creek and the Los Angeles River, and crisscrossed with numerous smaller streams.

All of these hills and waterways made Silver Lake a natural site for reservoir construction. The first in what’s now Silver Lake, was Reservoir No. 2, built in 1868 atop a stream bed that’s now entombed beneath Silver Lake Boulevard. Its dam was located near what’s now Sunset Boulevard and its northern shore would’ve been around what’s now Effie Street. It was followed by the Bellevue Reservoir in 1895, the Rowena Reservoir in 1901, and the Ivanhoe Reservoir in 1906.

Two hand-colored lantern slides of the Silver Lake Reservoir (Autry Museum of the American West)

The largest of them all, the Silver Lake Reservoir, was completed in March 1908. It entered service on 1 May of that year. When it opened, there was no fence because public access was not just permitted, it was encouraged. The reservoir was even stocked with black bass and hosted fishing annual competitions.

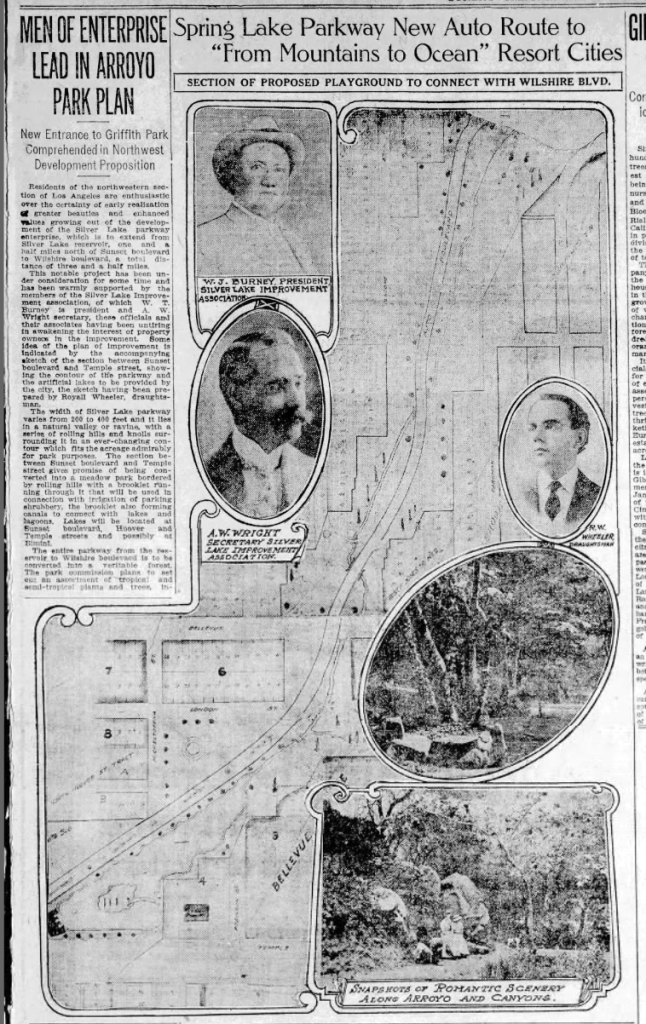

It was around 1911 that Angelenos began first referring to the surrounding community as Silver Lake instead of Ivanhoe or Edendale (although those names also remained in use for a time). It was also in 1911 that some began to refer to the neighborhood as “Silver Lake Park.” That year, plans were made to upgrade the reservoir complex into a gem of the park system. The park itself was to have been beautified. It was also to have served as the centerpiece of a series of parks connected by landscaped, scenic boulevards — or “parkways.” Initially more modest, the scope of the project eventually sought to connect Elysian Park, Griffith Park, Sunset Park (now Lafayette Park), Eastlake Park (now Lincoln Park), and Westlake Park (now MacArthur Park); with Silver Lake Park the literal centerpiece. If completed as planned, it was reported, it would form a “parkway system rivaling if not surpassing those of Cleveland and Seattle.”

Silver Lake Park was W. T. Burney, who formed the original Silver Lake Improvement Association in or shortly before 1913 (unrelated, except nominally, to the current organization of the same name). There was, inevitably, opposition to the project. The Los Angeles Times reported “The [City] council was crowded with supporters of the Silver Lake project and two or three opponents of the plan…” On 3 October 1911, City Council voted six to two in favor of the plan. Work got underway. The eucalyptus, conifers, and other trees were planted around the reservoir. After that, though, the momentum on the project seems to have ground to a halt, primarily due to insufficient funds. On 6 March 1918, City Council formally voted to abandon the project.

Although the Silver Lake Park plan was abandoned, people continued to enjoy access to the reservoir for the time being. The accessibility did not come without occasionally tragic costs. The first death in the reservoir was likely the 1910 suicide of William “Daddy” Richardson. There was also the accidental drowning in 1912 of a young, Benjamin Halprin. His father sued the city, afterward, insisting that the city install a fence around the water. The Assistant City Attorney countered that installation of a fence was unnecessary, though, and no fence was built. Two more unsupervised children, Arthur Donald Gordon and Orland Bernard Gordon, drowned in the reservoir in 1914.

Although more than a decade would pass in which there was no fence, swimming was banned in 1920. That year, at the urging of some of his vocal constituents, Socialist City Councilman Fred C. Wheeler introduced a motion at City Hall to “prohibit bathing in Silver Lake.” The Los Angeles Evening Post-Record reported that “This action should be taken, the resolution claims, not because the water is being polluted, as it is not used for domestic purposes, but for the reason that men and boys have been bathing in the lake garbed in nature’s clothing.” The skinny-dipping ordinance passed in August 1920 and the authorities were instructed to “take necessary action” to “prohibit the use of the Silver Lake Reservoir as a “swimmin’ hole’.”

Although swimming was no longer allowed, the reservoir continued to be promoted as a “fishin’ hole” for the time being. By then, it was stocked with bluegill black bass, Buffalo carp, and perch. The month of May kicked off the Municipal Fishing Season and the reservoir hosted an annual fishing contest until at least as late as 1919. There was still fishing at least as late as 1920, because that year several fishermen were charged with violating game laws by using immature bass as bait. 1921 was the first year that the reservoir was deepened and refilled. It was, afterward, restocked with fish but by 1922, fishing was banned. The fish had originally been introduced to control the grow of aquatic plants and algae blooms. In 1924, the reservoir was drained, yet again, so that a 36-inch water main could be installed to aerate the water, something it was hoped would do the job of the fish.

Without a fence, the ban on fishing and swimming relied solely on Angelenos’ respect for the law – and police enforcement of it. In 1924, plans were made to create Silver Lake Boulevard on the reservoir’s eastern shore. It wasn’t long before the first automobiles were plunging into the still-unfenced reservoir. In 1927, a stolen car was pulled from the waters near “Petting Row,” as an area along the southeastern shore was then popularly known.

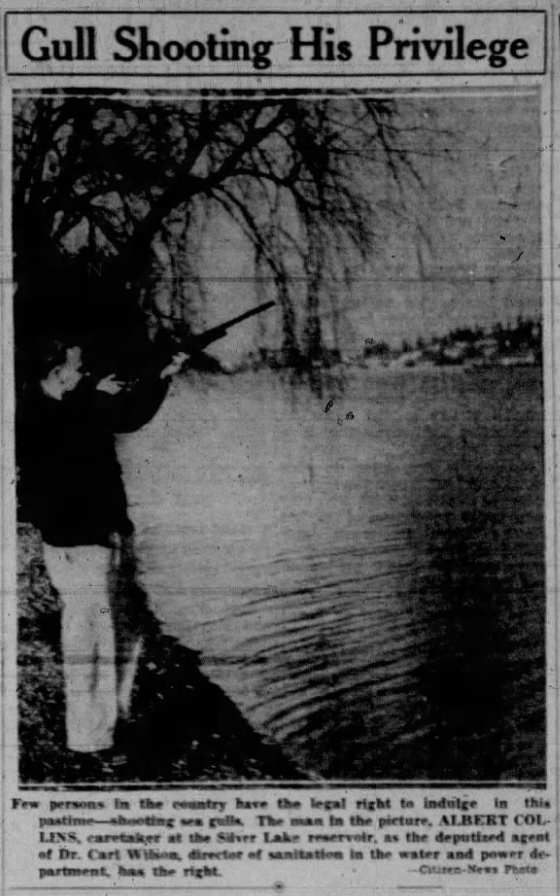

Although much of the discussion about the Silver Lake Reservoir today revolves around the wellbeing of wildlife, animal welfare was, historically, evidently a non-concern. In 1931, the Police Commission granted the caretaker/director of sanitation for the water and power bureau to fire blasts from his shotgun in order to keep mudhens, ducks, geese, gulls, and other birds from making “a bird resort out of the Silver Lake reservoir.” Although meant to just scare the birds, shotgun blasts aren’t exactly known for their pinpoint accuracy and if animals were harmed in the shooting of them, this was duly logged and recorded without the apparent shedding of any tears.

Around the same time that wildlife was being made to feel very unwelcome, access for humans was expanding on the southern end of the reservoir complex. Those plans include a new recreation center with tennis and croquet courts. The new recreation center was dedicated– as The Los Angeles Recreation Center at Silver Lake, East Hollywood – on 20 November 1931.

Within a few years, the rec center hosted a civic orchestra – the Silver Lake Recreation Center Band.

Above the recreation center, meanwhile, the reservoir itself was drained and expanded in 1932.

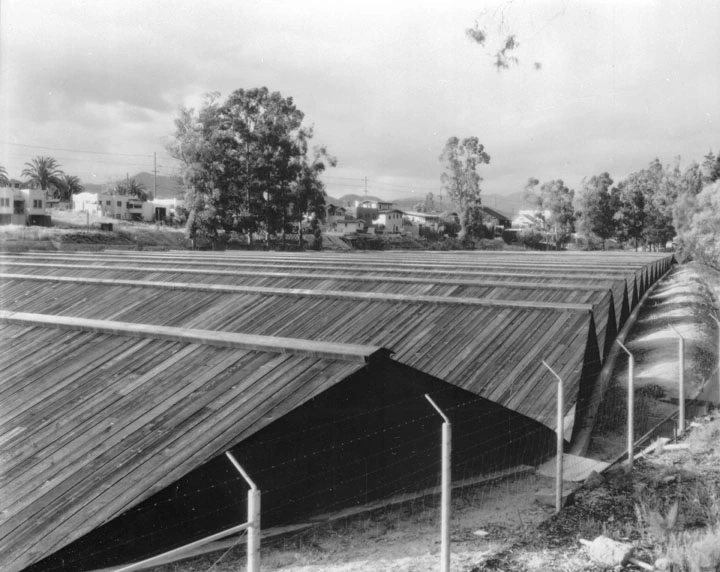

The smaller Ivanhoe Reservoir was covered with a structure made of wood and roofing material in order to protect the water quality.

Above the new recreation center, the top and perimeter of the south dam was planted with cypress and shrubs. There’s also a fence. It’s difficult to tell if it extends all of the way around the reservoir. A photo dated from 1936 shows a walking path on the eastern shore with no fence in sight (although it could just be out of frame). A photo by Herman Schultheis and dated “circa 1937” seems to depict the eucalyptus grove with no fence (and the south dam in the background).

Whatever the case, there was definitely a fence by 1941, when a volunteer l police force was charged with protecting the reservoir. Increasingly, it seems that the fence went up, then, in response to the country entering World War II — and due, in part, to fears actively stoked by the city’s leader.

The US entered the Second World War on 8 December 1941, after the the Imperial Japanese Navy bombed American military outposts Hawaiʻi and the Philippines. Republican Fletcher Bowron, then mayor of the city with the second-largest population of Japanese outside of Japan, used a radio address spread the rumor that Japanese Angeleno employees of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power were planning on poisoning the city’s water supply and urged their firing. An volunteer auxiliary police force was formed to protect the “vital military objectives,” including the Silver Lake Reservoir.

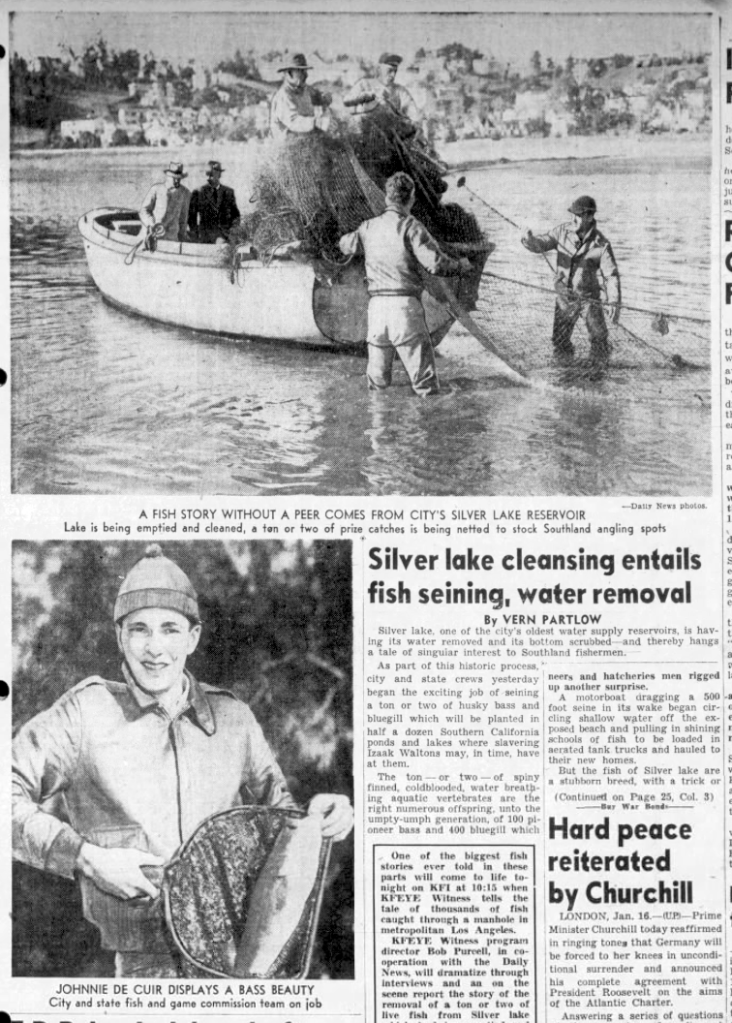

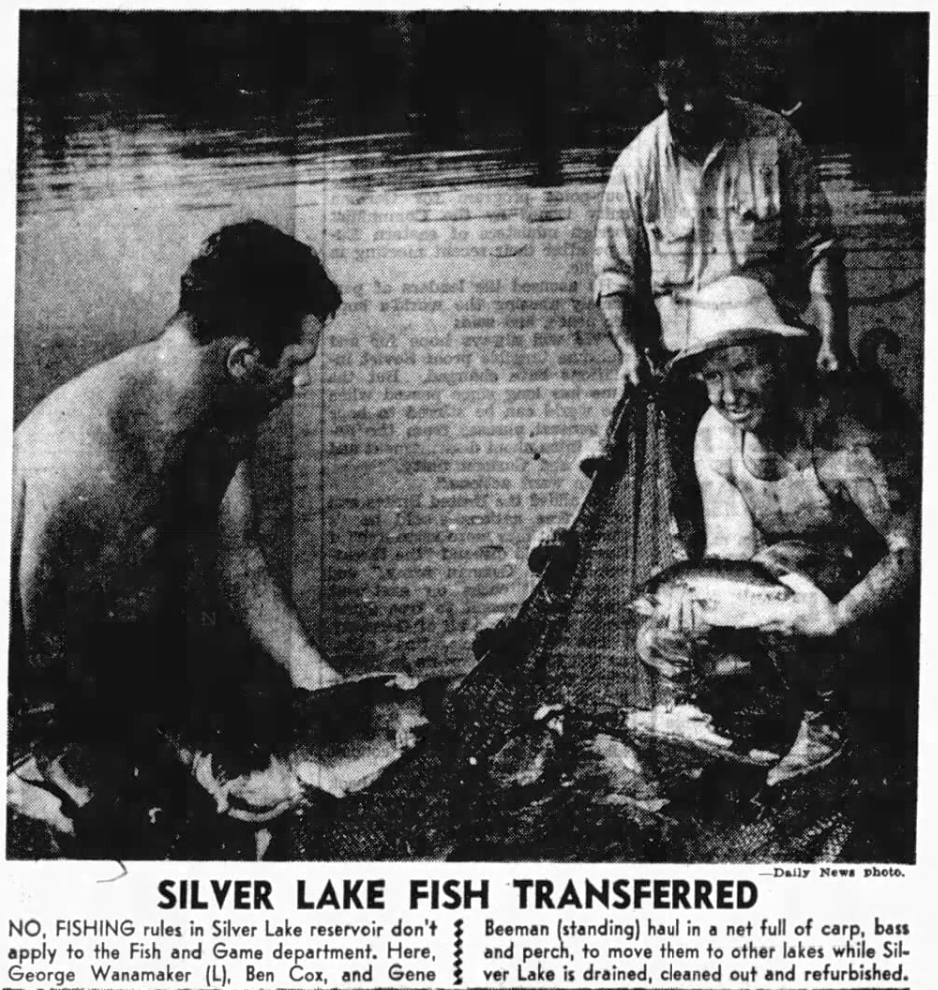

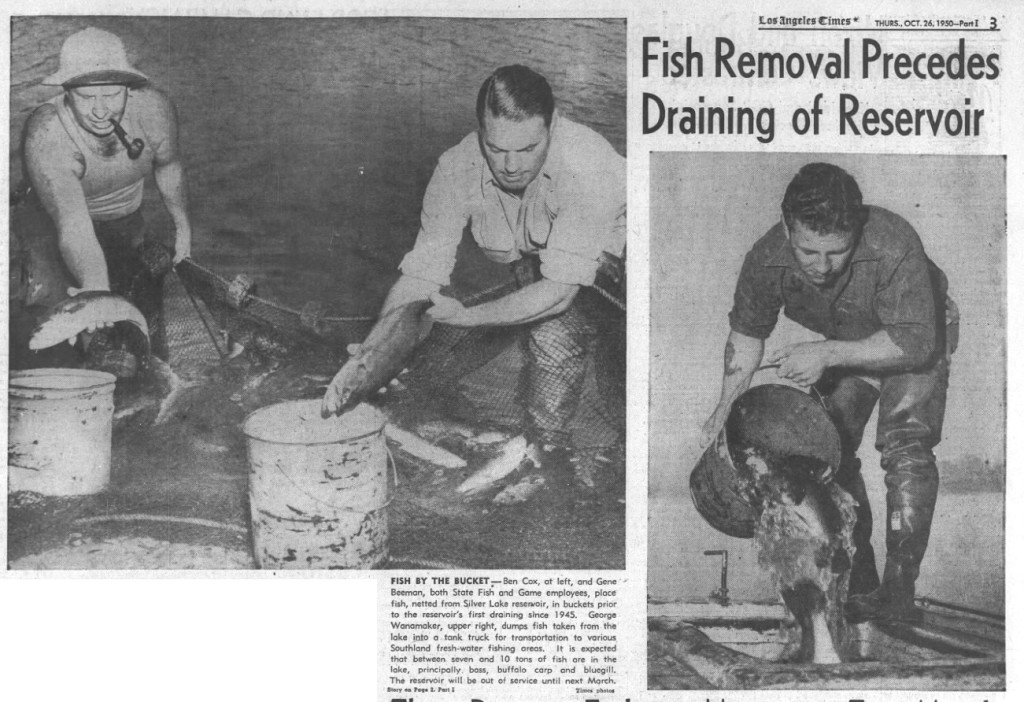

The post-war era brought big changes to the reservoir. When the reservoir was drained and refilled in 1945, the fish were relocated. A bigger project began in 1950, when plans were announced that the reservoir would be drained and deepened so that a new, 60-inch water main could be installed. The slopes would be made steeper and would be paved to control erosion — a task previously given to vegetation growing on the banks.

The fish were again relocated. This time, the newspapers offered the estimate that there were 100,000 – or seven to ten tons. Although the DWP promised their return, at least some were dumped into Ballona Creek. It seems unlikely that any returned, though — asphalt and concrete are not normally part of the piscine diet.

Concerned Silver Lakers, led by Helen Lee McKellar, organized the All Area Silver Lake Committee in 1952 to advocate for a more park-like reservoir instead of what the LADWP planned to build, which the committee described as a “big, boxy bathtub.” Gerald W. Weston, meanwhile, was the president of the newly-formed Silver Lake Beautification League – which demanded the restoration of trees and shrubs Father and son architects, Richard and Dion Neutra, were members of both organizations; and they submitted a master plan calling for the creation of contoured banks, landscaping, a reflecting pool, and other features.

The LADWP rejected the park designs and stated that they were “not in the park business.” The wooden roof was removed from the deepened Ivanhoe Reservoir, now deep enough for water to better circulate. The refilling of the Silver Lake Reservoir was completed in 1953. The DWP did partially concede in one area. The stagnant and shallow bay that the Neutras had suggested would make a nice park with a water feature, was filled and turned into a fallow and fenced off lawn.

Meanwhile, in the southwestern corner of Silver Lake, the Bellevue Reservoir was decommissioned in 1955 and it was announced that it would be turned into a park. A reported 250 Silver Lakers showed attended a hearing to voice their objections, which included the cost, noise, danger to children, and increased traffic. The LADWP transferred that property to the Department of Public Works, who began work on the project. The property was transferred to the Department of Recreation and Parks and the Bellevue Park and Recreation Center opened on 1 May 1959.

Back at the Silver Lake Reservoir, the current recreation center opened around 1966. The tennis court was converted to a basketball court. The croquet court vanished — although it would be revived, unofficially, by the Silver Lake Croquet League around 2000. Community organizations that formed in that decade, like the Silverlake Homeowners Protective Association, Silver Lake Homeowners Defense League, and Silverlake United Property and Homeowners were focused on fighting the construction of new housing rather than the reservoir. The oldest Silver Lake community organization, the Silver Lake Residents Association, was formed in 1968.

Although set in the San Fernando Valley, the Silver Lake Reservoir had an uncredited background role in the 1969 episode of Adam-12 titled “The Things You Do for the Job.” Later that year, a writer at The Los Angeles Evening Citizen News revived a question that hadn’t been asked — at least not widely — for quite a few years.

RENEWED RESERVOIR ACTIVISM

Community activists returned their gaze to the Silver Lake Reservoir complex in the decade that followed. The Magnitude 6.6 1971 San Fernando Earthquake struck on 9 February. Felt 300 miles from its epicenter, it resulted in the deaths of 65 people, the injury of more than 2,000, property losses of over half a billion. Perhaps, worst of all, it spawned another Hollywood disaster film George Kennedy film, Earthquake. In the wake of the crisis, the LADWP announced that they intended to rebuild the Silver Lake Reservoir dam in order to make it earthquake safe. The Committee to Save Silver Lake was formed in 1973 to oppose the reconstruction. The reservoir was, over CSSL’s objects, drained once again and a new, earthquake-safe dam was completed in August 1975.

In 1985, Michael K. Woo was elected to represent the Los Angeles City Council’s 13th District. One of his campaign promises was to install a jogging path around the reservoir. It wasn’t exactly a new idea. Although early visitors to the reservoir favored sauntering and strolling to jogging, there had been a path for them to do so around the reservoir at least as late as the 1930s (see above left). A path specifically for jogging, though, had been proposed at least as early as 1981, pushed by a gay men’s running club called the Frontrunners. There were inevitable objections. Anti-jogging path critics claimed that a jogging path would “shatter the neighborhood’s serenity” and serve as “a magnet for criminality.” Decades later, in 2016, Howie Goldklang co-founded the Silver Lake Track Club, participants of which run around the reservoir every Thursday and end at the Red Lion.

At the same time, the director of the Silver Lake Recreation Center began lobbying the LADWP to allow for the creation of a baseball diamond on the fenced off lawn east of the reservoir. The LADWP refused and so Caltrans leased a patch of its 2 Freeway off-ramp property for the creation of the Tommy LaSorda Field of Dreams.

In 1988, Sharon Flanagan formed the Committee to Save Silver Lake’s Reservoirs in order to stop the construction of a water filtration plant on the property. The committee later evolved into the Silver Lake Reservoirs Conservancy. Over time, the organization would take a significant role in numerous improvement projects. In 1989, the Ivanhoe and Silver Lake Reservoir Complex in Los Angeles was designated as Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 422 – right behind the designation of the Lake Hollywood Reservoir. It was also in 1989 that, in order to satisfy new EPA standards, the City of Los Angeles first proposed covering reservoirs in order to protect drinking water quality from the formation of bromate. Bromide (naturally present in water) can combine with ozone to create carcinogenic bromate when exposed to sunlight. Covered reservoirs, though, are generally regarded as unattractive – certainly less attractive than open ones. A compromise was reached with the Rowena Reservoir when it was covered with an attractive but publicly inaccessible landscape in 1991. Water features, trails, benches and landscaping were installed — but a high fence was installed to keep out all but the most determined. Meanwhile, the potentially hazardous water of Silver Lake’s reservoirs continued to be piped out of Silver Lake to homes in South Los Angeles and Downtown.

More access was granted to the complex in the 1990s. Jackie Goldberg – who succeeded Woo in 1993 — proposed creating a dog park on the hill east of the dam, then colloquially known as Dog Hill for its preponderance of canine visitors. When the Silver Lake Dog Park was dedicated in January 1995, it was only the second city-maintained dog park in the city. Thirty years later, I doubt many would object to my ranking of it, too, as one of the city’s worst. There is little greenery which allows dust clouds to befoul its surroundings and many visitors think nothing of parking their vehicles at red curbs and in bicycle lanes.

Calls for a dedicated jogging path took on a renewed urgency in 1995. On the evening of 11 June 1995, Milan-born Diane Manahan did what comes natural for a Milanese; she went on the passeggiata after dinner. A speeding motorist flew up West Silver Lake Drive. Manahan pushed her husband to safety but was hit and killed. The motorist, newly a grandfather, drove home and shot himself. Vocal opposition to the walking path seemed to evaporate. The pedestrian path was completed thirteen years later.

Fifty years after the rejection of the Neutras’ master plan, another architect firm had a crack it it, Mia Lehrer + Associates. It called the replacement of asphalt with plants, a reduction in the reservoir’s depth from 45 feet to 20 or 30 feet, the creation of the Silver Lake Meadow, and shifting the fence closer to the water’s edge to allow for more public access. It was approved by the LADWP in November 2000.

After stricter federal water quality rules were enacted, the Silver Lake Reservoir was phased out of use in 2006. After potentially dangerous levels of bromate were detected in the water, both the Ivanhoe and Silver Lake reservoirs were drained in 2007. Before it was refilled, though, the Ivanhoe Reservoir received a shipment of 400,000 black shade balls in order to combat bromate formation once refilled. When the walking path was finished in 2008, it was seperated from the reservoir by a new fence — the tallest one yet. After the opening of the walking path, the reservoir saw many more walker, strollers, and runners. Benches were installed along West Silver Lake Drive for riders of Metro‘s 201 Line, which connected to Los Angles’s more park-poor neighborhood — Koreatown — until it was discontinued in 2021. The benches remain.

The Mia Lehrer & Associates-designed 2.5-acre Silver Lake Meadow opened in April 2011. In 2011, the Silver Lake Neighborhood Council created the Silver Lake Reservoir Committee. The small, 280 square-feet Tesla Pocket Park opened in 2012. The reservoirs were disconnected from the city’s drinking-water system in December 2013. In January 2014, Catherine Geanuracos publicized her proposal for the Silver Lake Plunge, which called for turning the Ivanhoe Reservoir into a giant, municipal pool. She formed a group called Swim Silver Lake, which in 2017 evolved into Silver Lake Forward.

The reservoirs were drained again in 2015, to install a 4,600-foot long, 66-inch diameter welded steel pipeline and a new regulator station. They were refilled in April 2017 and then, that September, the Ivanhoe Reservoir was drained yet again. Another neighborhood activist, Jill Cordes, co-founded a group called Refill Silver Lake Now to demand that an accelerated refilling of the empty reservoir. After the reservoirs were refilled (minus Ivanhoe’s shade balls), they changed their name to Silver Lake Now. Another neighborhood activist, Freda Foh Shen, formed the Silver Lake Wildlife Sanctuary in 2018, which advocates for maintaining the decommissioned reservoir pretty much as is, for the sake of the wildlife that lives in or visits the complex. More public access to the complex would follow, though. In February 2018, a walking path atop the south dam was made open during daylight hours. The Ivanhoe Pathway opened in the northwest area that autumn, similarly open during daylight hours.

Another master plan was initiated in 2018, funded by the LADWP and managed by the Bureau of Engineering, In 2019, Hargreaves Jones was chosen as project’s landscape architect. In 2020, City Council voted to adopt the findings of a final Environmental Impact Report. In 2023, Silver Lake resident and Neighborhood Councilperson, Nikos Constant, filed a lawsuit against the City of Los Angeles, the City Council, and the Bureau of Engineering; alleging multiple violations and improprieties in the master plan process. In September 2024, Constant and Iris Schneider were elected to the co-chair roles in the Silver Lake Neighborhood Council’s Silver Lake Reservoir Complex Committee.

The reservoir’s future role in the community remains unwritten. If you have opinions about its present and future, though, consider attending meetings or joining the active community organizations mentioned here. Stay cool!

Comments