Black Pioneers of Silver Lake: History of Silver Lake's Early Black Community

- Eric Brightwell

- 1 day ago

- 10 min read

Updated: 3 hours ago

"Ask Silver Lake” is dedicated to exploring the history and insights of our community. If you have questions or ideas you’d like us to consider, please drop a comment or send them to outreach@silverlakenc.org.

Silver Lake, in its early years, was essentially off limits to black Angelenos. Unlike nearby Burbank and Glendale, it wasn’t a sundown town, but — like most of Los Angeles — it was comprised primarily of tracts whose homes included racially restrictive covenants that legally prevented their sale of most homes to non-Caucasian and non-Protestant Angelenos. Language in the deed to homes usually explicitly forbade their sale to — in the language of the day — “Asiatics,” “Hindoos,” “Malays,” “Mexicans,” “Mongolians,” “mulattoes,” “Orientals,” “Spanish Americans,” and “negroes.”

GEORGE WASHINGTON ALBRIGHT

There were notable exceptions. Black resident George Washington Albright, a former slave-turned-Mississippi state senator, moved with his white wife, Josephine Hardy, to the adjacent Dayton Heights community in 1892. The two planted an orchard, farmed, operated a mill, and successfully petitioned Los Angeles to open a school there, which it did, in 1910 — the Dayton Heights School (now Dayton Heights Elementary).

In 1914, Tsyua and Sukesaka Ozawa bought property in Dayton Heights which they operated as a boarding house for Japanese Angelenos. Before long, Dayton Heights was home to a thriving Japanese community and even came to be popularly known as “J. Flats.“ There are few obvious reminders of the Japanese character, today. There’s the Hollywood Japanese Cultural Institute, founded in 1915 as The Hollywood Buddhist Church. The Tenrikyo Hollywood Church was founded in 1929.

In the 1920s, however, anti-black racism came roaring back with a vengeance. In 1923, when a group of black would-be homeowners attempted to procure a lot of Dayton Heights framed by Maltman, Marathon, and Tularosa; the Dayton Heights Improvement Association mobilized to oppose them. The Los Angeles Times praised the association’s racist triumph as having stopped an “invasion.”

PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS

While blacks weren’t welcome to live in Silver Lake, they were, in the case of Paul Williams, allowed to design homes for white homeowners. One such architect was Paul Revere Williams — the first black architect to become a member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), which he did two years after becoming a certified architect in 1921. Williams was born in 1894 to two transplants from Memphis, Chester and Lila Williams. They lived in what’s now the Fashion District. When Paul was four years old, both of his parents died of tuberculosis. He was afterward adopted and raised by friends of his parents from the First African Methodist Episcopal Church. His older brother, Chester Williams Jr., was raised by another set of foster parents.

In 1933, French restaurateur Rene Faron wished to celebrate the fortunes of the restaurant, Rene & Jean, which he operated in what’s now the Financial District with Leon Bevillard and Jean Ibert. Faron commisioned Williams to design him a residence in Silver Lake’s Moreno Highlands, believing in Williams’s ability to design homes with an “instant historic presence.” Williams created a stately American Colonial Revival–style home (with Monterey and Mediterranean Revival elements) at 2003 Micheltorena Street. Construction began in March 1935 and was completed in 1937.

Whilst Williams helped shape Silver Lake’s built environment, he lived in a Craftsman home with his family in an area of Exposition Park that was free racial restrictions. It was changing around him. When he moved there in 1921, it was a largely Japanese enclave known as Seinan. By the 1930s, it was in the process of transforming into Los Angeles’s original Koreatown. After racist housing covenants were abolished, the Williams family moved to Lafayette Square, where Williams designed an International Style home in which he remained until his death in 1980.

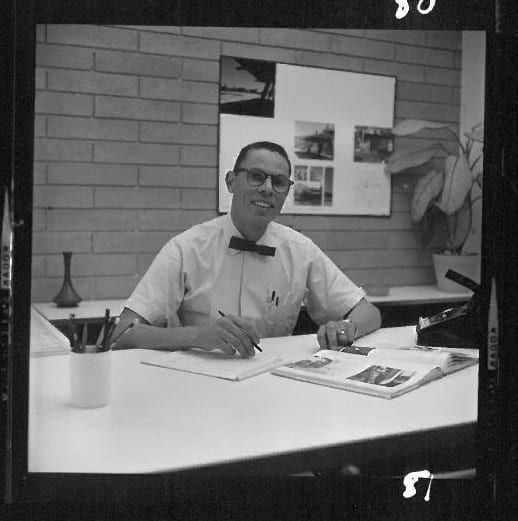

JAMES HOMER GARROTT, JR.

Three years after the completion of the Faron Residence, on 17 July 1940, owner Fannie Ellen Garrott was issued a building permit to erect a home just a block from the location where black homeowners had been defeated by the Dayton Heights Improvement Association in 1923. The architect of the home would be her son, James Homer Garrott, Jr.

Homer was a transplant who was born in Montgomery on 9 June 1897 to James Homer Garrott, Sr. and Fannie Garrott (née Walker). He had one brother, Curtis Walker Garrott, and together they moved to Los Angeles where James Jr. graduated from Los Angeles Polytechnic High School in Sun Valley in 1917. James Garrott, Sr. died in 1918.

Six years after high school, Garrott began working with Pasadena architect, George P. Telling. From 1926 to ’28, Garrott worked with Cavagliere Construction Company of Los Angeles during which time he earned his architect’s license. In 1928, he also co-designed the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company‘s headquarters with Louis Blodgett (added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998) in South Central. In 1929, he teamed with Paul Williams to design St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, also in South Central. Garrott attended the University of Southern California from 1930 to 1934. In 1936, he designed Mount Zion Baptist Church. He also designed the residence of Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company board chairman George A. Beavers, Jr. In 1940, Garrott and Pittsburg-born architect Gregory Ain opened an architectural practice in Westlake‘s Granada Building known alternately as Garrott & Ain and Ain & Garrott.

Compared to some of Garrott’s more striking modernist homes, the home he designed for his family — at least the exterior — is fairly nondescript — architecturally modest, even — and I have to wonder if this was by design, necessity, or for some other reason (or combination of reasons). Garrott also built the similar-looking home next door, at 647 North Michetorena Street. The building permit for it was issued to Juanita E. Miller on 13 August 1940 — less than a month after the permit was issued for the Garrott family home.

LOREN MILLER

Juanita Miller was the wife of Loren Miller, an outspoken journalist, activist, and civil rights attorney who’d been born in Pender, Nebraska in 1903. His father had been born into slavery. His mother was a German-Irish woman from Stoutland, Missouri. When still a boy, the Miller Family moved to Kansas where, in 1928, Miller earned his Bachelor of Laws degree and was admitted to the Kansas State Bar. In 1929, Miller moved to Los Angeles, where he wrote and edited the famous black newspaper, The California Eagle. In 1933, he was admitted to the California State Bar. In 1944, Miller won the court case of Fairchild v. Raines, in which a black family purchased a non-restricted home in Pasadena but were nevertheless sued. The following year, he represented Ethel Waters, Hattie McDaniel, and Louise Beavers — three black Hollywood entertainers who’d encountered resistance when they attempted to procure homes for themselves on West Adams Heights‘ Blueberry Hill. Miller and his clients prevailed, and before long the neighborhood was better known as Sugar Hill neighborhood — named after the affluent Hamilton Heights section of West Harlem.

In 1945, J. D. Shelley and Ethel Lee Shelley, a black couple in St. Louis, Missouri, attempted to buy a home with a racist covenant that restricted its sale to “people of the Negro or Mongolian Race.” A white couple, Louis and Fern Kraemer — who could hardly be described as neighbors since they lived ten blocks away — objected. The case of Shelley v. Kraemer went to the US Supreme Court in 1948. Loren Miller was the chief counsel for the Shelleys, who prevailed. The court ruled that racist housing covenants were unconstitutional. It was one of the most important steps in the decades long progress of dismantling racial segregation across the nation. Miller purchased The California Eagle, from Charlotta Bass in 1951. It was published until 1964, the year governor Pat Brown appointed Miller to the Los Angeles County Superior Court. In 1966, Miller wrote The Petitioners: The Story of the Supreme Court of the United States and the Negro. Miller still lived in Silver Lake when he died on 14 July 1967.

Garrott found that there were few opportunities for him as a black architect and he worked, during the Second World War, at Douglas Aircraft factory in Santa Monica. Garrott’s fortunes began to change, however, in 1946, when he became the second black architect admitted to the American Institute of Architects | Los Angeles. His application had been co-sponsored by Ain and Williams. In 1949, the re-teamed Ain and Garrott (or Garrott and Ain) designed themselves a beautiful new Mid-Century Modernist architectural office at 2311 Hyperion Avenue on the boarder of Silver Lake and Los Feliz. As a team, Garrott and Ain went on to design the Ben Margolis House (for the defense attorney best known for defending the Hollywood Ten and the Sleepy Lagoon murder suspects), the Westchester Municipal Building, the Loyola Village Branch Library, and the Ralph Atkinson Residence.

Ain and Garrott often offered input on one another’s projects, even when credited as sole designers. Credited as sole architect, Garrott designed the M. Wesley Farr Residence in El Segundo, the Jesse and Ruth Oser House in Brentwood, the Verna Deckard and John W. Bean House in West Adams Terrace, the Firestone Park Sheriff’s Station, the Lawndale Administrative Center, the Bodger County Park Director’s Building in Alondra Park, the Del Aire County Park Director’s Building, the Victoria Park Pool and Bathhouse in Carson, the Carson Public Library, and many others. He also designed another Silver Lake home, in 1953, for Harry I. Friedman and Bernice “Burr” Lee Singer.

Burr Singer was a social realist painter who had been born in St. Louis, Missouri on 18 November 1912. She studied art at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts and, later, at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Art Students League in New York City, and in private classes with Walter Ufer in Taos. Although white, her paintings were largely concerned with black subjects, whom she often depicted in lithography, oil, and watercolor portraits. Garrott’s design at 2143 Panorama Terrace is a Mid-Century Modernist stunner. Garrott died on 9 June 1991. Burr Singer died on 18 November 1992, Artist Jed Lind and his wife, stylist Jessica de Ruiter, bought the home in 2010 and restored it. In 2023, it was purchased by Zack de la Rocha.

ROBERT KENNARD

The final home in this essay is another Mid-Century Modernist stunner — this one at 2076 Redcliff Street. It was built in 1964 and designed by Robert Kennard. Robert Alexander Kennard was born in 1920 in Los Angeles to Marie Bryan and James Kennard – a former Pullman porter. When he was four, his family moved to Monrovia, where they lived “south of the tracks” in the town’s black enclave, Little Africa. On his mother’s insistence, young Robert daily crossed the tracks to walk to the de facto whites-only Wild Rose Elementary (now Wild Rose School of Creative Arts), only to be turned away everyday. After a couple of weeks, the Kennards acquired a lawyer and the school district compromised, allowing him to attend the Orange Avenue School, despite its also being otherwise de facto segregated until 1970.

Some of Kennard’s teachers at integrated Monrovia High were more accepting – encouraging his gift for drawing. One teacher introduced him to the work of Paul Willams and Kennard began pursuing an interest in architecture. Whilst enrolled at Pasadena Junior College, Kennard and another black discipled of Williams, Benjamin McAdoo, won the first and second place in the PJC Architectural Design competition. Hoping to apprentice, Kennard instead found himself rejected repeatedly by architecture firms on account of his being black. In 1940, he was hired by H. Curtis Chambers. After serving in the Second World War, however, he enrolled at the USC School of Architecture on a GI scholarship.

In 1949, Richard Neutra offered Kennard an apprenticeship but Kennard passed because he deemed the wage of $50 per month too meager to support a family. Kennard was hired by Robert E. Alexander in 1950, however, and the latter formed a partnership with Neutra, so Kennard became a project designer for the firm of Neutra & Alexander. During this tenure, Kennard served as the project designer for the planned $35-million redevelopment project, Elysian Park Heights, which ultimately did not materialize due to mounting right wing opposition to public housing. Kennard left the firm in 1953 and in 1954 designed his first solo project, the Sommers House in Beverly Hills. He started his own firm, Kennard Design Group, in 1957 – today the oldest black-owned architecture firm in Los Angeles.

Kennard’s early focus was on private residences, such as Zeiger Residence in Laurel Hills (1958), his own family residence in Hollywoodland (1961), and the striking Susan Hardyman Residence on Redcliff, built for radical Leftist activist and philanthropist, Susan Isham Hardyman, who then lived at a Carl Maston-designed home across the reservoir on Duane Street. The home on Redcliff, like many Mid-Century Modernist home in the hills, is noted for its rear orientation which offers views of the Silver Lake Reservoir through a sweeping, curved wall of glass panels. Unfortunately, the home is difficult to see from Kenilworth, below. The view from the front only hints and the home’s considerable charms. Hardyman sold the home in 1974. It was for sale again in 2006 and Michael Locke took a nice picture of the east side of the home at that time. It was purchased by Dane Taylor in 2006. Sadly, the 46-year-old Taylor died in 2025 and since then, the street-facing landscape has been denuded of life but for a single tree, giving the home a decidedly bleak appearance.

Kennard shifted his focus first into encouraging and mentoring young black and other minority architects. In 1969, he founded the Southern California Association of Minority Architects and Planners (MAP). In 1971, MAP was succeeded by the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA) formed in Detroit, by Kennard along with eleven other black architects. Kennard later turned his focus to public architecture, designing buildings like Pasadena’s Scott United Methodist Church (1975), Carson City Hall (1976, with Robert Alexander and Japanese architect, Frank T. Sata), the Van Nuys State Office Building (1985, with Compton City Hall and Civic Center architect, Harold L. Williams), and the Jesse A. Brewer 77th Street Regional Headquarters in Florence. The latter was completed in 1997, two years after Kennard died. In 2019, the AIA|LA honored his legacy with the creation of the Robert Kennard, FAIA Award for Equity, Diversity & Inclusivity.

FURTHER READING

“Monrovia Superstar: Architect Robert Kennard” by Susie Ling (2019, Monrovia Weekly)

Comments